The Core Principle: "Railways as a Means to an End"

|

| JR East E657 series EMU set K-1 near Kita-senju Station on a test-run on the Joban Line |

For these companies, the railway line itself is often not the primary profit center. Instead, it is the catalyst that increases the value of land and creates captive customer flows for their other businesses. The railway makes remote, undervalued land accessible and desirable, and the company captures the resulting economic value.

The Historical Development Model (The "Garden City" Approach)

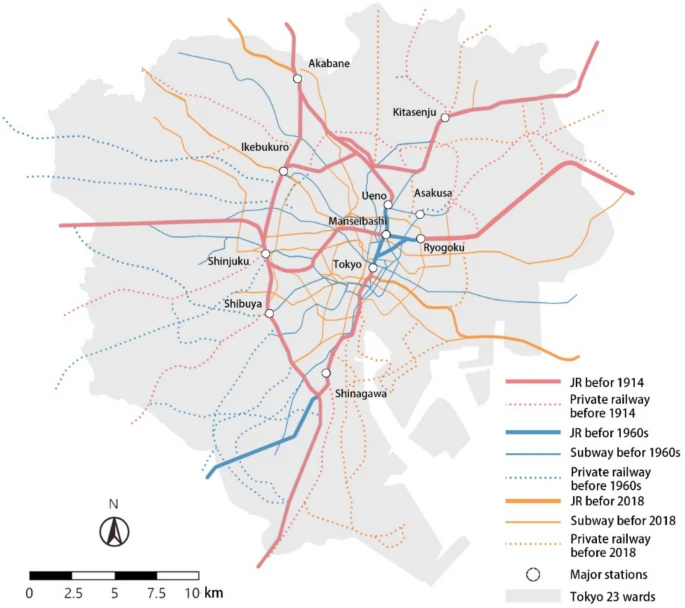

This model took off in the early 20th century, particularly in the rapidly growing metropolitan areas of Tokyo and Osaka.

1. Land Acquisition: A railway company would purchase large, cheap tracts of agricultural land far from the city center.

2. Railway Construction: They would build a rail line connecting this land to the city center.

3. Development & Value Creation: They would then develop the land around their stations:

- Residential: Suburban housing communities ("danchi") for commuters.

- Commercial: Department stores (often right above or adjacent to the terminal station, e.g., Tokyu Store at Shibuya, Hankyu Store at Umeda).

- Leisure: Amusement parks (e.g., Tobu Zoo Park, Seibu's Tamako Park), resorts, hotels, and golf courses along the line.

4. Ridership Guarantee: The residents of these communities become daily commuters, guaranteeing a stable ridership for the railway. The shoppers and leisure seekers provide additional weekend and holiday ridership.

This creates a powerful, self-reinforcing cycle: Better development attracts more riders → More riders justify better train service (more frequent, express trains) → Better service increases land value and attracts more development.

|

| matcha-jp.com |

Key Examples of Major Conglomerates

- Tokyu Corporation: The archetype. Developed much of southwest Tokyo (Shibuya, Den-en-chofu) and Kanagawa. Its empire includes Tokyu Land (real estate), Tokyu Store (retail), and Tokyu Hotels.

- Hankyu Hanshin Holdings: Pioneered by Ichizo Kobayashi, who famously said, "The railway is the hardware, and the content it carries is the software." He built the Hankyu line from Osaka to the suburb of Takarazuka, developing housing and creating the famed Takarazuka Revue all-girl theater troupe to attract riders. The flagship Hankyu Department Store at Umeda Station is iconic.

- Keio Corporation and Keisei: Major players in western and eastern Tokyo, respectively, with extensive real estate and retail operations.

- Tobu Railway: Dominates the northern Tokyo area and Tochigi, with massive developments, the Tokyo Skytree, and resorts like Nikko.

- Seibu Group: Developed western Tokyo and Saitama, with flagship department stores, the Prince Hotel chain, and professional baseball teams (the Saitama Seibu Lions).

Modern Evolution: "Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) on Steroids"

The model has evolved but remains central. Today, it focuses on creating "terminal cities" or "ekinaka" (within-station) economies.

1. Station as a Destination: Major terminals (like Shibuya Stream developed by Tokyu, or Osaka Station City developed by JR West) are no longer just transit points. They are integrated complexes of offices, luxury hotels, high-end retail, cinemas, and public spaces.

2. Capturing Passenger Flow: By owning the station building and adjacent structures, the railway company directly monetizes the flow of passengers through rent, retail sales, and food & beverage.

3. Synergy Across Sectors: A company can leverage all its divisions for a single project:

- Railway Division: Provides transport access.

- Real Estate Division: Develops the offices and residences.

- Retail Division: Operates the department store and specialty shops.

- Leisure Division: Runs the hotel and cinema.

|

| Ticket vending machines on the Omori JR Station |

Why This Model is So Successful in Japan

- Deregulation: Japan's land use laws are relatively flexible, allowing for mixed-use development around stations.

- High Rail Reliance: Dense populations and cultural preference for public transit ensure strong ridership.

- Integrated Corporate Structure: A single corporate group can coordinate all aspects of planning, avoiding the conflicts common between separate transport and property entities.

In Contrast: Public vs. Other Private Railways

- Japan Railways (JR): Formerly national, now privatized. Some JR companies (especially JR East) have adopted similar real estate strategies (e.g., redeveloping Tokyo Station's GranRoof and KITTE mall), but their history and land holdings differ from the classic private developers.

- Subways & Public Lines: Many municipal subway lines primarily focus on transport and lack the vast land holdings for large-scale development, though they do engage in station-area commerce.

Summary

Japanese private railway companies are real-estate developers that happen to own a railway. The railway is the strategic infrastructure that creates value in their land holdings and delivers customers directly to their commercial properties. This symbiotic, closed-loop system is a key reason for the efficient, dense, and commercially vibrant urban landscape found around train stations throughout Japan.